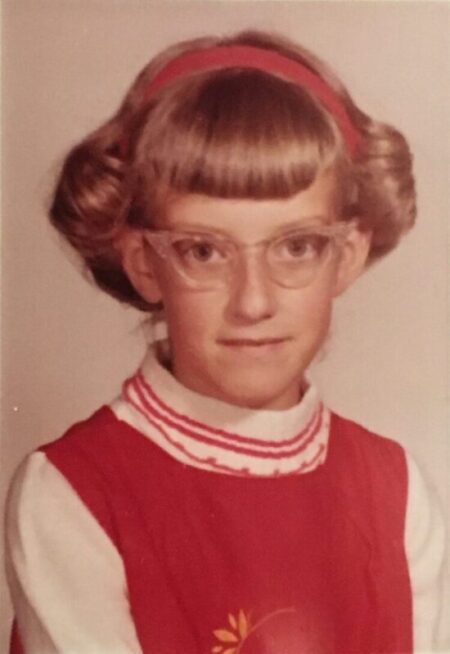

The early years

Pam’s parents noticed she was having trouble with her vision around the age of 2. An ophthalmologist saw that her lenses were already nearly completely dislocated then; she was prescribed “coke-bottle glasses”. Then at the age of 12, she switched to contacts and was astounded at how much she hadn’t been seeing until then. “For the first time in my life, I could see the leaves on trees, and I could read things that weren’t too far away. It was a life changer for me.”

While in elementary school, Pam tended to need a little extra help, always sitting in the front row and staying with a tutor after class. “But I did fine,” Pam says. “My parents’ philosophy was always ‘Do the best you can, and as long as you’re doing the best you can, you know that’s all we ask of you.’”

Pam’s family thought she had Marfan syndrome. Marfan syndrome is a genetic condition that affects the body’s connective tissue and can cause issues in many parts of the body including the heart, bones, joints, and eyes. Dislocated lenses are common in Marfan syndrome, and people with the disorder tend to be very tall like Pam is. In ninth grade, Pam began having problems with scoliosis, yet another common Marfan syndrome symptom.

What didn’t quite add up is that Pam wasn’t experiencing any heart issues, which is common in Marfan syndrome. But the diagnosis still seemed the best fit with what the family knew and what Pam was facing. “My parents were always really good about searching out the best people they could find to help me with the different issues that I was experiencing.”

After high school, Pam attended the University of Nevada, Reno. She joined a sorority, succeeded in college, and graduated with a teaching degree in special education. In her third year of work, she describes the day that she went to school with “a little curtain going across my left eye.” By the end of the day, she had no eyesight in that eye. The school nurse was too nervous to tell Pam what she thought was wrong.

Still just in her 20s, she underwent surgery to repair her detached retina followed by numerous (technologically early) laser surgeries to help restore her vision.